Israeli art has always found itself pulled in two conflicting directions; the need to address what was happening outside, and the desire to focus on the autonomous concerns of art itself, of material, method, and definition. Moreover, it has always developed in a complex context of socio-political tension, war, and bloodshed, a context in which it is impossible to separate everyday individual life from the historical and the mythical. Art’s response to this loaded reality is complex. Initially, in the first decades of the 20th century, many Jewish artists were unable to see or unwilling to portray that complexity; instead, they painted an idealistic, optimistic, and often naïve picture that reflected their hopeful vision of the future.

Reuven Rubin’s famous painting First Fruits is a good example. Rubin drew the land as an Oriental paradise, a place of harmony and fertility – the perfect setting for the birth of a new kind of Jew and the shaping of native Israeli identity. Alongside these artists, others expressed social and political engagement through their art, depicting a more sober reality in an attempt to bring about change. Naftali Bezem’s To the Aid of the Seamen refers to the seamen’s strike which broke out in 1951 and triggered heated debates on Israel’s kibbutzim over whether or not to support the strike.

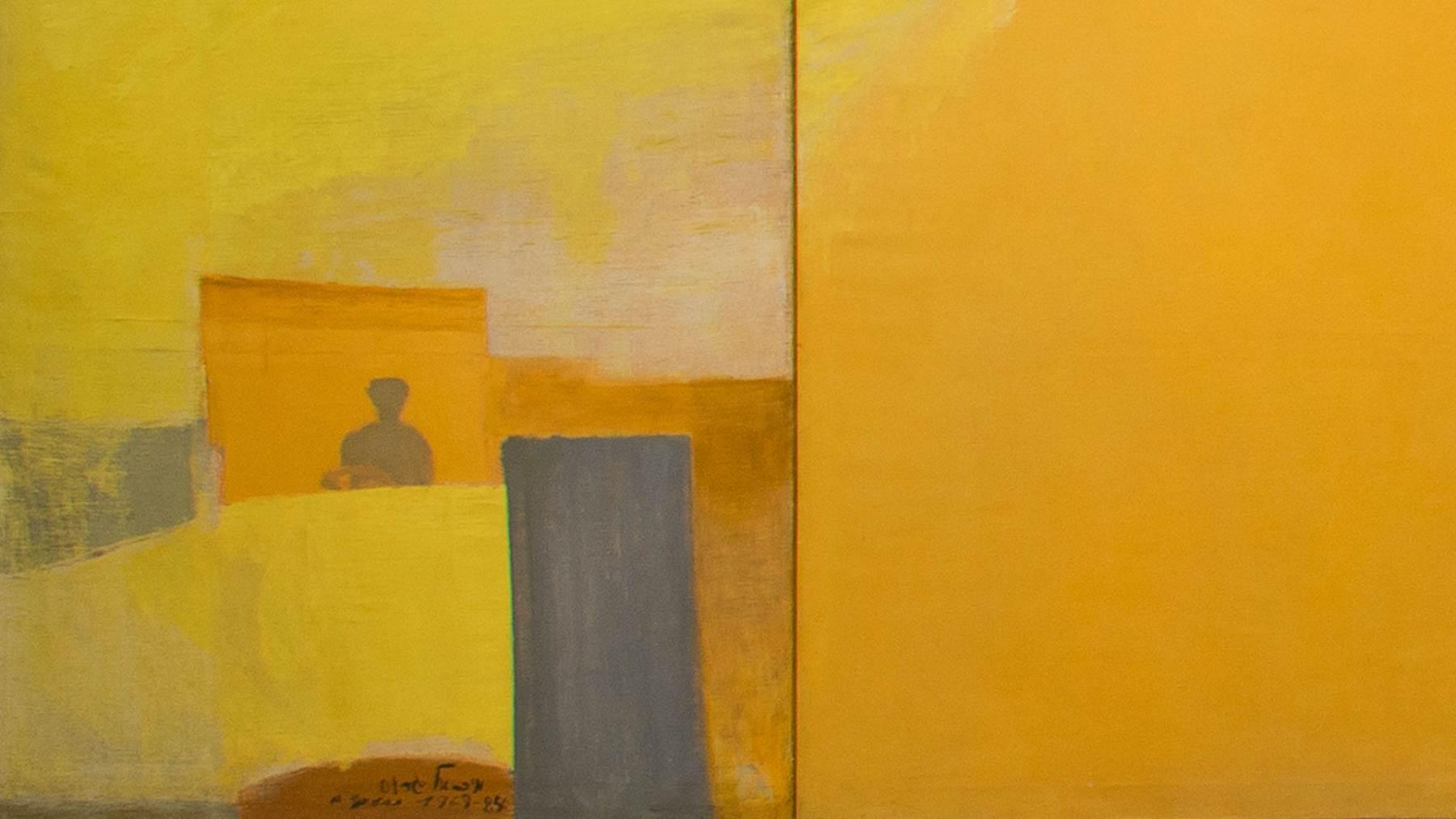

The commitment to art for art’s sake was a powerful force, with many artists devoting themselves to composition, line, color, and material in an attempt to define the relationship between visible reality and a creative act that articulates the artist’s innermost spirit. Yosef Zaritsky’s Yehiam is a good example. The indistinct human figures he inserted in the composition resemble patches of vegetation, and they communicate a tension between the natural and the human, between figuration and abstraction. Many artists straddled both camps. Their multilayered work combines personal and collective concerns. Such is Larry Abramson, who drew on newspapers from June 1967, the time of the Six-Day War, a black square, a skull, outlines of plants and planks, cracks and fragments.

The motifs have been a staple of his work for many years alongside images referencing art histories – such as Malevich’s avant-garde black square and the skull which symbolizes human mortality, take on new meaning when read against a chronicle of national events that would forever change the face of Israel.